22th April 2022 – Pesach is here

And this emails reaches you one day before because this evening the last two days of Pesach start. Let’s celebrate with Syrian Jewish music.

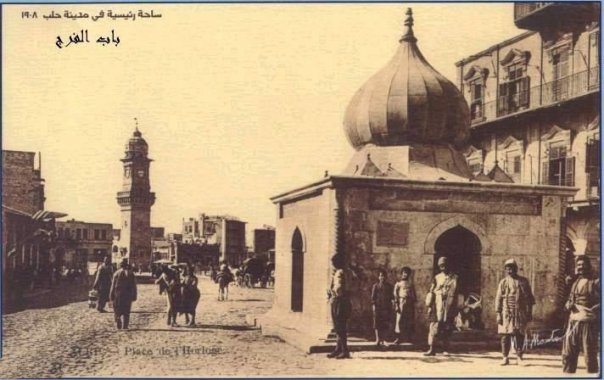

Hello, I hope you are well and enjoying this special time of Pesach. Today we will listen to some Syrian Jewish music. The current situation in Ukraine is attracting a great deal of attention and MBS could not fail to condemn the invasion and to support, even in as small a capacity as this weekly newsletter has, Ukrainian culture in some way from the point of view that guides us here, that of Jewish culture wherever it is or has been found throughout history. This should not prevent us from remembering other catastrophes that continue to cause so much pain today. Yemen comes up here often. The richness of the legacy of Yemeni Jewish music well justifies it. Syria remains, so many years later, another source of human shame and horror. I read in DW that in 2013 more than 100,000 people were killed in the war in Syria and that in 2014 the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights stopped counting casualties because of insufficient access to combat zones. The bombing continues to this day.

Hello, I hope you are well and enjoying this special time of Pesach. Today we will listen to some Syrian Jewish music. The current situation in Ukraine is attracting a great deal of attention and MBS could not fail to condemn the invasion and to support, even in as small a capacity as this weekly newsletter has, Ukrainian culture in some way from the point of view that guides us here, that of Jewish culture wherever it is or has been found throughout history. This should not prevent us from remembering other catastrophes that continue to cause so much pain today. Yemen comes up here often. The richness of the legacy of Yemeni Jewish music well justifies it. Syria remains, so many years later, another source of human shame and horror. I read in DW that in 2013 more than 100,000 people were killed in the war in Syria and that in 2014 the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights stopped counting casualties because of insufficient access to combat zones. The bombing continues to this day.

And I read on the Radio Sefarad website, in a 2015 post, “There are no more Jews in Syria”. A secret operation was organised to evacuate the last remaining Jews, ending a history of more than 3,000 years of Jewish presence in the land.

The picture is of public domain, I got it from here and it is described as a “photograph of a Jewish wedding in the Middle East 1904. The Jewish marriages are celebrated with great pomp, the nuptial feast continuing seven days. The bride is accompanied by her mother and near relations, and the ceremony is performed in the presence of as many, beside those invited, as can find room in the house; for there is always a number of Turkish and Christian women among the spectators. The Castle band of musicians is employed the first day, and, on the subsequent days they have chamber music, dancers, and buffoons.”

In today’s MBS we will remember the Jews of Syria, with a piece of music appropriate for Pesach, and we will also discuss the concept of pizmonim.

Then, please, spread the word.And note that these weekly emails are also posted in the website www.musicbeforeshabbat.com

| Share this with a friend, right from here |

About the artists: Aram Soba Orchestra with Maury Blanco

The band that is our protagonist today seems not to have been active for a long time. Their Facebook posts date back to 2006 and I can’t find any more recent information. I found their brief bio on the Pizmonim.org website:

The band that is our protagonist today seems not to have been active for a long time. Their Facebook posts date back to 2006 and I can’t find any more recent information. I found their brief bio on the Pizmonim.org website:

“The Aram Soba Orchestra was founded by Maury and Josh Blanco in 2014 with the goal of reviving the songs of the Aleppo community in a form that appeals to the contemporary listener. The orchestra focuses on preserving the pizmonim of Shir Ushbaha Hallel Vezimrah, particularly those written to the adwar of Egypt and Syria. In an effort to portray the beauty of these works to the modern listener, the orchestra arranges them to convey their full array of dynamics, with a twenty-piece ensemble of ten instruments and ten singers. By recording these treasures in a contemporary form, The Aram Soba Orchestra makes this beautiful art accessible once again. May this project provide a taste of the music of the past, and may it assist in bringing the songs of old to the ears and lips of the new.”

I really wonder if the “contemporary listener” might have a problem with the way music was interpreted decades ago. I’m really tired of this tendency of some artists to have to justify themselves with the idea that they modernise or update the music to make it fit today’s times. I personally usually find recordings from 60, 70, 80… years ago more appealing. I’m sure I’m not the only one. Another question is whether most of today’s artists are capable of interpreting like those of the past, which would be another matter for another analysis. But well, apart from that, it’s an interesting recording and it is a pity that they have not shown signs of life more recently.

I looked up these gentlemen Blanco, Josh and Maury, and I believe they are from Baltimore, from two references: this testimonials page on a music teacher’s website and this condolence page on the website of the Beth Tfiloh Dahan Community School. But I haven’t found any other bio, Facebook or useful LinkedIn profiles.

But in this text there are some other ideas to explore.

What are the pizmonim?

I found today’s piece on the Sephardic Pizmonim Project website. There you find that:

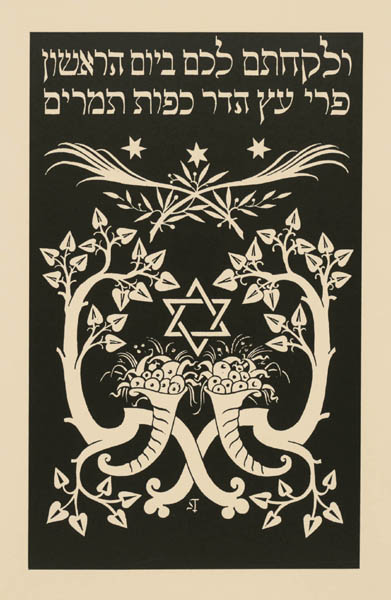

“For at least a thousand years, since before the days of the Mahzor Aram Soba (1527, 1560), and before that in Spain, praising God through poetry, namely “piyyut,” and song, namely “pizmonim,” has become a major foundation for Middle Eastern Jews in how they approach worship.”

S0, what is the Mahzor Aram Soba?

On the website of the Gross Family Collection – The center or Jewish Art, I found this very interesting text by William Gross:

“The printing press arrived to the Jewish Community in Aleppo surprisingly late, not before the year 1865. This may be due in part to their neighbors’ religious beliefs, Islam’s view of the printing press, “It would be an act of impiety if the word of God should be squeezed and pressed together; but the true cause was, that great numbers of themselves earned a considerable income by transcribing those books” (Quarterly Review XLI 1829 Page 475). Before the arrival of the printing press in Aleppo, the Jewish Community would send their books mostly to Europe to be printed, in the 16th and 17th century for the most part to Venice, later on to Amsterdam and Constantinople and from the 18th century on, mainly to Livorno, Italy. The first known book to be sent from Aleppo to be printed was the Mahzor Aram Soba, printed in Venice in 1527.”

On the website of the Gross Family Collection – The center or Jewish Art, I found this very interesting text by William Gross:

of the Gross Family Collection – The center or Jewish Art, I found this very interesting text by William Gross:

“The printing press arrived to the Jewish Community in Aleppo surprisingly late, not before the year 1865. This may be due in part to their neighbors’ religious beliefs, Islam’s view of the printing press, “It would be an act of impiety if the word of God should be squeezed and pressed together; but the true cause was, that great numbers of themselves earned a considerable income by transcribing those books” (Quarterly Review XLI 1829 Page 475). Before the arrival of the printing press in Aleppo, the Jewish Community would send their books mostly to Europe to be printed, in the 16th and 17th century for the most part to Venice, later on to Amsterdam and Constantinople and from the 18th century on, mainly to Livorno, Italy. The first known book to be sent from Aleppo to be printed was the Mahzor Aram Soba, printed in Venice in 1527.”

The reference of the Quaterly Review can be found here.

So, it must be a very important book. What is its content? According to the SephardicHeritageMuseum’s website:

“As Spanish exiles settled throughout the Middle East, the liturgy of the Mustabarim began to fall into disuse in favor of the Sephardic version of prayers. To preserve their unique liturgy, Aleppo’s Mustabari community published a siddur – the Mahzor Aram Soba – in 1527. It was reprinted in 1560, but with the passage of time, most of the Aleppan community developed a prayer service comprised of elements from both the Mustabari and Sepharadi traditions […] Throughout its long history, the city of Aleppo has had many names. […[ The name Aram Soba was used by the rabbis and hachamim of Aleppo to refer to the city in their documents and manuscripts.”

Ok, so it is the mahzor (or maḥzor) from the city of Aram Soba/Aleppo. What is a mahzor? According to the JewishEncyclopedia:

“Term applied to the compilation of prayers and piyyuṭim; originally it designated the astronomical or yearly cycle. By the Sephardim it was used for a collection which contains the prayers for the whole year while the Ashkenazim employed it exclusively for the prayer-book containing the festival ritual.“

But wait a moment. What are the Mustabarim? Once more, according to the website of the SephardicHeritageMuseum’s website:

“The original Jews in Aleppo and the other Jewish communities in the Middle East were known as Mustarabim. The term “Mustarabim” connotes that they resembled Arabs. These native-born Jews’ customs, dress and mannerisms, as well as their accent, were similar to those of the Arabs, among whom they lived.”

And, what is the Shir Ushbaha Hallel Vezimrah?

It is the first book of pizmonim edited by the Sephardic congregation of Brooklyn. The editor was Gabriel A Shrem, who was the great grandfather of David Matouk Betesh DMD, the founder of the Sephardic pizmonim project. About Shrem, this website explains that he was born in Cairo in 1916. His maternal uncle Abraham Chehebar taught him pizmonim and Hazzanut. He immigrated to the United States in 1930. And explains that: “In 1941, Gabriel and his family permanently moved to Bensonhurst in Brooklyn, New York. He was offered the position of Cantor at the Betesh Synagogue (“Knis Betesh”), and several years later, in 1945, he began his tenure at Magen David of 67th Street, where he faithfully served until 1963 as their senior cantor.

In the 1950s, Gabriel teamed up with Mr. Sam Catton of the Sephardic Heritage Foundation to publish the community’s first Pizmonim book, “Shir Ushbaha Hallel VeZimrah”.

There is only one word that I haven’t found: adwar. It appears on the bio of the band, as “adwar of Egypt and Syria”. This only appears all over the internet on this bio page. I don’t know if this is a typo.

About the piece

The website of the Sephardic Pizmonim Project is organiced by several criteria, like the maqam and the festival where it is used. I have chosen one for Pesah. About it, the website explains that it is:

“a song that is very popular. H Raphael Tabbush is likely the author of this pizmon, but this is uncertain. The melody of this song is from the Arabic song “Baladi Askara Min Araf il Lama.” This song is associated with the Shalosh Regalim festivals due to a brief reference to them. The melody of this pizmon is typically applied to Shav’at Aniyim for weeks of Maqam BAYAT. Despite this being a song for the most happy of holidays, this song is actually very sad. It asks why has God abandoned us and why has the Messiah not yet arrived? It describes how our enemies have taken over our vineyards and have killed us. The climax of the song, “Al Damam,” describes how “my tears fall on their blood” (the blood of fellow Jews) and how our tears are enough to fill rivers. The four verse piece concludes with an open question: “Where has my Beloved gone; to Whom I rejoice three times a year?”.

Let’s clarify some terms:

- The Shalosh Regalim are the three pilgrimage festivals: Pesach, Shavuot and Sucot.

- Here you are a bio of Hakham Raphael Tabbush.

- You can listen to the mentioned Arabic song Baladi Askara Min Araf il Lama on several renditions on Youtube, one of the best is this one by Sheikh Sayyed El Safti.

- Shav’at Aniyim is a zemirot song.

It’s time to enjoy the music.

Click the picture to listen to Maury Blanco and the Aram Soba Orchestra performing Sa Liznuhakh:

Shabbat Shalom & Pesach Sameach