8th April 2022 – Shabbat is almost here

And today we will listen to a dance tune recorded at a Hassidic wedding and we’ll understand the meaning of music for the Hassidism.

Hello. I hope you are well. Pesach is coming soon and I have already planned the piece for next week but today I wanted to find out more about an idea that has appeared in MBS before: which is the vision of the music by the Hassidism? Maybe it’s not a question you ask yourself every day but I do. Let’s answer it.

| Share this with a friend, right from here |

About the Hassidism and the music

Today when I woke up the question came to me and I searched and immediately found a YIVO page that explains the answer at length. It’s a bit long and very very interesting, I recommend you read the whole thing. I’ll bring here just a few bits and pieces:

“Joy and its expression through song and dance have been important values of the Hasidic movement since its beginnings in the second half of the eighteenth century. The idealization of music reflected an innovation in Jewish culture, in contrast to the general attitude of the Ashkenazic rabbinical establishment. […]

In early Hasidic writings, magical and theurgical conceptions rooted in theosophical kabbalistic doctrine prevailed. These conceptions hold that human deeds, including musical activity, have the power to affect the godhead—and, as a result, the entire world. Later generations abandoned the view that every Jew can influence the divine world with music and restricted this ability only to the tsadik.”

So, what is a tsadik? According to Chabad.org, “The personality of the tzaddik is calibrated to the Manufacturer’s original specifications, so that everything about him is just as his Creator meant it should be, and all he desires is what his Creator desires. A tzaddik is one who embodies the Creator’s primal conception of the human being. […] The tzaddik is a human being like all of us. Because, essentially, all of us are divine.”

Let’s read more from YIVO:

“[…] there is a movement from dependence of music on text, especially prayer text, toward the belief that music can act in its own right, whether connected to a text or not. In consequence, Hasidic nigunim (sg., nigun; Yid., nign; spiritual melodies; in Hasidic terminology nigun can refer broadly to “music” as well as to a tune or composition) are typically sung without words. […] Adapting tunes from surrounding non-Jewish cultures is a hallmark of Hasidic music. The leading sages offered different understandings of this phenomenon of musical acculturation, even giving it the force of a religious duty. […] A more typical view holds that sacred melodies in gentile music have been, as it were, taken captive by evil forces in the constant struggle between divine forces and the forces of evil. These captive tunes—or, rather, the “holy sparks” hidden within them—await redemption. Tsadikim and their emissaries, wherever they lived, constantly sought out melodies with a “sacred flavor,” in order to “redeem the sparks” and restore them to their heavenly source.”

The work The Hasidic Nigun – Ethos and Melos of a Folk Liturgy, by Hanoch Avenary (in Journal of the International Folk Music Council Vol. 16 (1964), pp. 60-63) connects the relevance of the music not only to the Hassidism, but also to the previous mystical movements, like “The Pious of Ashkenaz” from the late twelfth century and the mystical doctrines from Safad after the expulsion from Spain. He explains that:

“All these movements differ from the more exlusive, speculative Cabala in stressing and esoteric way of life, and supplying practical guidance suited to everybody. They aim at a daily life brought close to God by striving for joy in His service, and for a complete merger of personality in esctatic prayer. These are the main motives for the preference given to musical expression. Words were regarded as a medium which was insufficient for grasping the secrets of cabalistic theosophy, and for the exalted feelings of union with the endlss and absolute. There are sayings such as “Silence is better than words, but singing is better than silence”, or “There are castles in the upper spheres which open only to song”. […] There is a mystic idea that also tunes are in exile, and may be liberated by leading them back to serve a holy purpose. Consequently, all the doors were opened to the influx of foreign musical forms and styles, but they were remodelled. There is a tendency to suggest in song a gradual rise from the depths of this world to the higher spheres of the transcendent, to holy joy, enthusiasm, ecstasy. This may be achieved by means of gradually raising the pitch level of the same motive, by abrupt changes in, or continuous acceleration of, time, by obstinate repetition of short motives, by the introduction of unusual intervals, and so on.”

The rest of this work is very interesting and accesible in Jstor for independent researchers.

And what about nowadays?

The music we will listen to today is not new. It was recorded in the 70s. For me, it is wonderful music, as many other wonderful musics I use to listen to, as I work with world music in the agency and with several other initiatives. The Jewish music is for me also a way of learning about history, places and a culture that, in my country, Spain, is almost unexistent. But while searching for more about the Hassidism and the music I found the article Hasidic music: Pushing the boundaries of the Israeli comfort zone, by By Merav Livneh-Dill, that talks about the current actitude of the non-Haredi people towards the “Hassidic music”. It has shown me a totally different point of view from mine. If you are interested in this topic, be sure to read it.

About the piece

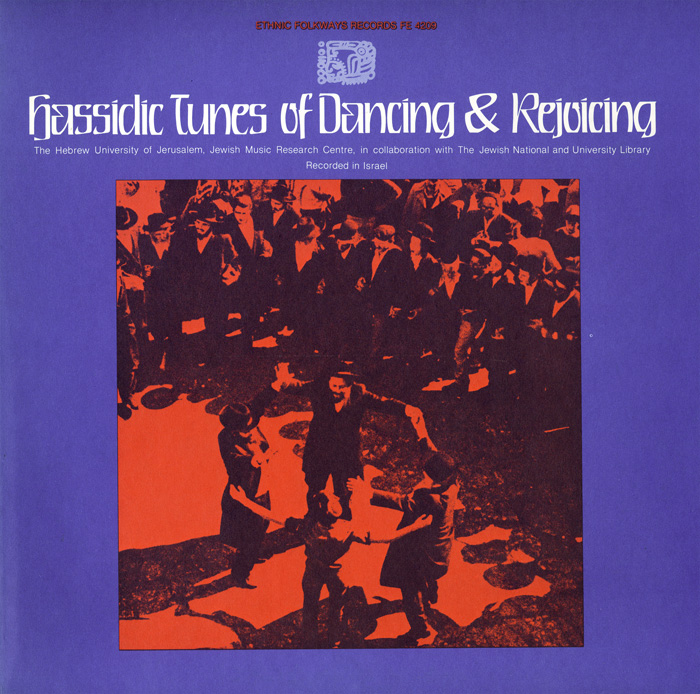

The piece we will listen to today is included in the album Hassidic Tunes of Dancing and Rejoicing, released in 1978 by Smithsonian Folkways. It is the first issue in the Anthology of Musical Traditions in Israel by the Hebrew University Jewish Music Research Centre. Here you can listen a sampler of the pieces and access the full booklet. The album is very nice and I will come back to it at some point, especially on Lag Ba’omer.

The piece we will listen to today is included in the album Hassidic Tunes of Dancing and Rejoicing, released in 1978 by Smithsonian Folkways. It is the first issue in the Anthology of Musical Traditions in Israel by the Hebrew University Jewish Music Research Centre. Here you can listen a sampler of the pieces and access the full booklet. The album is very nice and I will come back to it at some point, especially on Lag Ba’omer.

About this specific piece it explains that:

“This tune is sung to the common circle dance by Hassidim of various ‘dynasties’ in the Mea Shearim quarter and its neighbourhoods in Jerusalem. As with a number of other tunes, its origin is a bone of contention between the Karlin and the Slonim Hassidim.

The Near-Eastern flavour of the melodic patterns suggests the possibility that the tune was adopted from some oriental source, Arab or Jewish. Such an influence is also recognizable in a number of other tunes of Hassidic communities in Israel, such as Karlin, Slonim and Bratslav.”

It is interesting to come back to the page of YIVO to further explore this issue of the music from the different dynasties. It explains that:

“Some dynasties have a repertoire of their own; others partly share a common repertoire; while a few mainly use nigunim from the general “pan-Hasidic” inventory, which are known in Yiddish as velts-nigunim (lit., “world” nigunim).

[…] There are indeed a few characteristic features that can be associated with the music of specific dynasties. For example, the brief dance nigunim of Bratslav and Karlin Hasidim have a simple structure and narrow range. […[ In many Hasidic communities, one element of community singing is a gradual but continuous rise in pitch, sometimes to impressive proportions (as among the Hasidim of Boyan, Lubavitch, and Slonim).”

The origin of the Slonim Hassidism is the city of Slonim when it was part of Lithuania (now it is Belarus). According to the Jerusalem Post, and quoting Professor Menachem Friedman, a Bar-Ilan University sociologist and Jewish historian and one of Israel’s leading authorities on haredi society:

“Slonim are typical Ashkenazi hassidim,” […] “in the 19th century the rabbi ordered part of the court to immigrate to Israel,” Friedman said. The Hassidim settled in Tiberius, alongside Karlin Hassidut. This move is what afforded the continuity of the Slonim Hassidut, whose larger Eastern European branch was decimated in the Holocaust. […] In the middle of the 20th century, after the leadership of the Hassidut had been reestablished in Israel, the court moved to Jerusalem, and built a new yeshiva on the outskirts of Mea She’arim.”

And this was the synagogue from outdoors in 2006. Picture from Wikimedia by user Unomano:

You can learn more about this synagogue in the website of the Virtual Shtetl.

The booklet continues explaining something that has driven me quite mad. I have bought the piece to check if it was not complete on the Youtube, but it is. On Youtube it is exactly the same as I had when buying. The text explains that:

“The tune is presented here in two renditions. The first is sung more slowly than usual by two Slonim Hassidim who are not dancing. The characteristic vocal style of the slow tunes of the Slonim Hassidim is evident, with its shifting intonation, chromaticism and slow glissando. The second performance was recorded during a dance of a heterogeneous crowd of Hassidim.

A. Recorded in Jerusalem, spring 1968. Michael and Elbanan Silber. Slonim Hassidim, at the home of Michael Silber, NSA no. Yc lenj7.

B. Recorded at a Hassidic wedding. NSA no. Yxc 22/ 14.”

What you will listen to below is the part B. Where is the A part? It is here. There must be a mistake in the booklet and on the website of Smithsonian, because this piece, the A, is called “Rejoicing tune to Lo Tevosi” but the booklet describes something totally different. In any case, you can listen the rendition A here (the one by Michael and Elbanan Silber) and the B, recorded at a Hassidic wedding, below.

Click the picture to listen to a Hassidic dance tune:

Shabbat Shalom

Araceli Tzigane | Mapamundi Música

And we share with you one hour of music for joy in this playlist.

To know more about our artists, click here.

May you always find the light in your path.